IELTSFever Academic Reading Test 87 With Answers ( Passage 1 The Sound of Dolphin, Passage 2 We have Star performers! Passage 3 Sunset for the Oil Business ) we prefer you to work offline, download the test paper and blank answer sheet.

For any query regarding the Academic IELTS Reading Test 87, you can mail us at [email protected], or you can mention your query in the comments section. Or send your questions on our IELTSfever Facebook page. Best of luck with your exam

Question PDF IELTSFever-academic-reading-test-87.pdf

For Answers Academic IELTS Reading Test 87 Answers

Reading Passage 1 Academic IELTS Reading Test 87

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on the Academic IELTS Reading Test 87 Reading Passage 1 below.

The Sound of Dolphin

{A} Each and every dolphin has a different sound just like you and me, a sound that other dolphins recognize as a particular individual. Even a new baby dolphin, (calf), can detect its mother’s whistle within the pod soon after birth. Utilizing their blowholes, air sacks, and valves, dolphins can emit a very wide variety of sounds. In fact, the frequency levels range 10 times beyond what humans can hear.

{B} This system is called “Echolocation”, or “Sonar”, just like what a submarine uses to navigate while underwater. Yet the dolphin’s sonar is much more advanced than human technology and can pinpoint exact information about its surroundings ranging from size, distance, and even the nature of the object.

{C} Millions of years ago, toothed whales developed echolocation, a sensory faculty that enabled them to survive in often murky and dark aquatic environments. It is a process in which an organism probes its environment by emitting sounds and listening to echoes as the sounds bounce off objects in the environment. With sound traveling better in water than electromagnetic, thermal, chemical, or light signals, it was advantageous for dolphins to evolve echolocation, a capability in which acoustic energy is used, in a sense, to see underwater. Synonymous with the term “sonar” (sound navigation and ranging) and used interchangeably, dolphin echolocation is considered to be the most advanced sonar capability, unrivaled by any sonar system on Earth, man-made or natural.

{D} Dolphins identify themselves with signature whistles. However, scientists have found no evidence of a dolphin language. For example, a mother dolphin may whistle to her calf almost continually for several days after giving birth. This acoustic imprinting helps the calf learn to identify its mother. Besides whistles, dolphins produce clicks and sounds that resemble moans, trills, grunts, and squeaks. They make these sounds at any time and at considerable depths. Sounds vary in volume, wavelength, frequency, and pattern. Dolphins produce sounds ranging from 0.25 to 150kHz. The lower frequency vocalizations (0.25 to 50 kHz) are likely used in social communication. Higher frequency clicks (40 to 150 kHz) are primarily used in echolocation. Dolphins rely heavily on sound production and reception to navigate, communicate, and hunt in dark or murky waters. Under these conditions, sight is of little use. Dolphins can produce clicks and whistles at the same time.

{E} As with all toothed whales, a dolphin’s larynx does not possess vocal cords, but researchers have theorized that at least some sound production originates from the larynx. Early studies suggested that “whistles” were generated in the larynx while “clicks” were produced in the nasal sac region. Technological advances in bio-acoustic research enable scientists to better explore the nasal region. Studies suggest that a tissue complex in the nasal region is most likely the site of all sound production. Movements of air in the trachea and nasal sacs probably produce sounds.

{F} The process of echolocation begins when dolphins emit very short sonar pulses called clicks, which are typically less than 50-70 millionth of a second long. The clicks are emitted from the melon of the dolphin in a narrow beam. A special fat in the melon called lipid helps to focus the clicks into a beam. The echoes that are reflected off the object are then received by the lower jaws. They enter through certain parts of the lower jaw and are directed to ear bones by lipid fat channels. The characteristics of the echoes are then transmitted directly to the brain.

{G} The short echolocation clicks used by dolphins can encode a considerable amount of information on an ensonified object – much more information than is possible from signals of longer duration that are emitted by manned sonar. Underwater sounds can penetrate objects, producing echoes from the portion of the object as well as from other surfaces within the object. This provides dolphins with a way to gain more information than if only a simple reflection occurred at the front of the object.

{H} Dolphins are extremely mobile creatures and can therefore direct their sonar signals on an object from many different orientations, with slightly different bits of information being returned at each orientation; and since the echolocation clicks are so brief and numerous, the multiple reflections from internal surfaces return to the animal as distinct entities and are used by the dolphin to distinguish between different types of objects. Since they possess extremely good auditory-spatial memory, it seems that they are able to “remember” all the important information received from the echoes taken from different positions and orientations as they navigate and scan their environment. Dolphins’ extremely high mobility and good auditory spatial memory are capabilities that enhance their use of echolocation. With much of the dolphin’s large brain (which is slightly larger than the human brain) devoted to acoustic signal processing, we can better understand the evolutionary importance of this extraordinary sensory faculty. Yet no one feature in the process of echolocation is more important than the other. Dolphin sonar must be considered as a complete system, well adapted to the dolphin’s overall objective of finding prey, avoiding predators, and avoiding dangerous environments.

{I} This ideal evolutionary adaptation has contributed to the success of cetacean hunting and feeding and their survival as a species overall. As a result, dolphins are especially good at finding and identifying prey in shallow and noisy coastal waters containing rocks and other objects. By using their sonar ability, dolphins are able to detect and recognize prey that has burrowed up to 1 1/2 feet into the sandy ocean or river bottoms – a talent that has stirred the imagination (and envy) of designers of manmade sonar.

{J} Researchers, documenting the behavior of Atlantic dolphins foraging for buried prey along the banks of Grand Bahama Island, have found that these dolphins, while swimming close to the bottom searching for prey, typically move their heads in a scanning motion, either swinging their snout back and forth or moving their heads in a circular motion as they emit sonar sounds. They have been observed digging as deep as 18 inches into the sand to secure prey. Such a capability is unparalleled in the annals of human sonar development.

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1? In boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet, write

| TRUE | if the statement is True |

| FALSE | if the statement is false |

| NOT GIVEN | If the information is not given in the passage |

[1} Every single dolphin is labeled by a specific sound.

{2} The system a dolphin uses as the detector could give a whole picture of the observed objects.

{3} Echolocation is a specific system evolving only for animals living in a dim environment.

{4} The sounds are made only in the area related to the nose.

{5} When producing various forms of sounds, dolphins have asynchronism as one characteristic.

Questions 6-8

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

Write your answers in boxes 6-8 on your answer sheet.

Question 6 What feature do the sounds deep in the water emitted by dolphins possess?

(A) diverging

(B) tri-dimensional

(C) piercing

(D) striking

Question 7 Which makes the difference between the dolphins and man when it comes to the treating of vocal messages?

(A) an acute sense of smell

(B) a bigger brain

(C) a flexible positioning system

(D) a unique organ

Question 8 Which is the undefeatable characteristic of the sonar system owned by dolphins compared with the one humans have?

(A) making more accurate analysis

(B) hiding the hunted animals

(C) having the wider range in frequencies

(D) comprising more components

Questions 9-13

Summary

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than three words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 9-13 on your answer sheet.

| Whether …………….. exists or not has not been confirmed yet. ………10……… is the bond between the baby dolphin and its mother. What’s more, ………11……… which are like different sounds made by humans are also used by dolphins. The sounds are made at a certain level of depth within a specific scope from a higher frequency aimed at communicating to a lower one to echolocate. Sounds are vital to dolphins living in deep waters while……12……. is not that imperative. Similar to all toothed whales, vocal cords do not exist in ……….13……..but it produces some sound. The tissue in the nasal area is perhaps to do with the sound production. |

Passage 2 Academic IELTS Reading Test 87

We have Star performers!

{A} The difference between companies is people. With capital and technology in plentiful supply, the critical resource for companies in the knowledge era will be human talent. Companies full of achievers will, by definition, outperform organizations of plodders. Ergo, compete ferociously for the best people. Poach and pamper stars; ruthlessly weed out second-raters. This in essence has been the recruitment strategy of the ambitious company of the past decade. The ‘talent mindset’ was given definitive form in two reports by the consultancy McKinsey famously entitled The War for Talent. Although the intensity of the warfare subsequently subsided along with the air in the internet bubble, it has been warming up again as the economy tightens: labor shortages, for example, are the reason the government has laid out the welcome mat for immigrants from the new Europe.

{B} Yet while the diagnosis – people are important – is evident to the point of platitude, the apparently logical prescription – hire the best – like so much in management is not only not obvious: it is in fact profoundly wrong. The first suspicions dawned with the crash to earth of the dot-com meteors, which showed that dumb is dumb whatever the IQ of those who perpetrate it. The point was illuminated in brilliant relief by Enron, whose leaders, as a New Yorker article called ‘The Talent Myth’ entertainingly related, were so convinced of their own cleverness that they never twigged that collective intelligence is not the sum of a lot of individual intelligence. In fact, in a profound sense, the two are opposites. Enron believed in stars, noted author Malcolm Gladwell, because they didn’t believe in systems. But companies don’t just create: ‘they execute and compete and coordinate the efforts of many people, and the organizations that are most successful at that task are the ones where the system is the star’. The truth is that you can’t win the talent wars by hiring stars – only lose it. New light on why this should be so is thrown by an analysis of star behavior in this month’s Harvard Business Review. In a study of the careers of 1,000 star-stock analysts in the 1990s, the researchers found that when a company recruited a star performer, three things happened.

{C} First, stardom doesn’t easily transfer from one organization to another. In many cases, performance dropped sharply when high performers switched employers and in some instances never recovered. More success than commonly supposed is due to the working environment – systems, processes, leadership, accumulated embedded learning that are absent in and can’t be transported to the new firm. Moreover, precisely because of their past stellar performance, stars were unwilling to learn new tricks and antagonized those (on whom they now unwittingly depended) who could teach them. So they moved, upping their salary as they did – 36 percent moved on within three years, fast even for Wall Street. Second, group performance suffered as a result of tensions and resentment by rivals within the team. One respondent likened hiring a star to an organ transplant. The new organ can damage others by hogging the blood supply, other organs can start aching or threaten to stop working or the body can reject the transplant altogether, he said. ‘You should think about it very carefully before you do a transplant to a healthy body.’ Third, investors punished the offender by selling its stock. This is ironic since the motive for importing stars was often a suffering share price in the first place. Shareholders evidently believe that the company is overpaying, the hiree is cashing in on a glorious past rather than preparing for a glowing present, and a spending spree is in the offing.

{D} The result of mass star hirings as well as individual ones seem to confirm such doubts. Look at County NatWest and Barclays de Zoete Wedd, both of which hired teams of stars with loud fanfare to do great things in investment banking in the 1990s. Both failed dismally. Everyone accepts the cliche that people make the organization – but much more does the organization make the people. When researchers studied the performance of fund managers in the 1990s, they discovered that just 30 percent of the variation in fund performance was due to the individual, compared to 70 percent to the company-specific setting.

{E} That will be no surprise to those familiar with systems thinking. W Edwards Deming used to say that there was no point in beating up on people when 90 percent of performance variation was down to the system within which they worked. Consistent improvement, he said, is a matter not of raising the level of individual intelligence, but of the learning of the organization as a whole. The star system is glamorous – for the few. But it rarely benefits the company that thinks it is working. And the knock-on consequences indirectly affect everyone else too. As one internet response to Gladwell’s New Yorker article put it: after Enron, ‘the rest of corporate America is stuck with overpaid, arrogant, underachieving, and relatively useless talent.’

{F} Football is another illustration of the stars vs systems strategic choice. As with investment banks and stockbrokers, it seems obvious that success should ultimately be down to money. Great players are scarce and expensive. So the club that can afford more of them than anyone else will win. But the performance of Arsenal and Manchester United on one hand and Chelsea and Real Madrid on the other proves that it’s not as easy as that. While Chelsea and Real have the funds to be compulsive star collectors – as with Juan Sebastian Veron – they are less successful than Arsenal and United which, like Liverpool before them, have put much more emphasis on developing a setting within which stars-in-the-making can flourish. Significantly, Thierry Henry, Patrick Vieira, and Robert Pires are much bigger stars than when Arsenal bought them, their value (in all senses) enhanced by the Arsenal system. At Chelsea, by contrast, the only context is the stars themselves – managers with different outlooks come and go every couple of seasons. There is no settled system for the stars to blend into. The Chelsea context has not only not added value, it has subtracted it. The side is less than the sum of its exorbitantly expensive parts. Even Real Madrid’s galacticos, the most extravagantly gifted on the planet, are being outperformed by less talented but better-integrated Spanish sides. In football, too, stars are trumped by systems.

{G} So if not by hiring stars, how do you compete in the war for talent? You grow your own. This worked for investment analysts, where some companies were not only better at creating stars but also at retaining them. Because they had a much more sophisticated view of the interdependent relationship between star and system, they kept them longer without resorting to the exorbitant salaries that were so destructive to rivals.

Questions 14-17

The reading Passage has seven paragraphs A-G.

Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter A-G, in boxes 14-17 on your answer sheet.

(14) One example from non-commerce/business settings that a better system wins bigger stars

(15) One failed company that believes stars rather than system

(16) One suggestion that the author made to acquire employees than to win the competition nowadays

(17) One metaphor to human medical anatomy that illustrates the problems of hiring stars.

Questions 18-21 Academic IELTS Reading Test 87

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1? In boxes 18-21 on your answer sheet, write

| YES | if the statement agrees with the writer |

| NO | if the statement does not agree with the writer |

| NOT GIVEN | if there is no information about this in the passage |

(18) McKinsey who wrote The War for Talent had not expected the huge influence made by this book.

(19) Economic conditions become one of the factors which decide whether or not a country would prefer to hire foreign employees.

(20) The collapse of Enron is caused totally by an unfortunate incident instead of the company’s management mistake.

(21) Football clubs that focus on making stars in the setting are better than simply collecting stars.

Questions 22-26

Summary

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than two words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 22-26 on your answer sheet.

| An investigation carried out on 1000 22 ……….. participants of a survey by Harvard Business Review found a company hiring 23 ……….. has negative effects. For instance, they behave considerably worse in a new team than in the 24 ……….. that they used to be. They move faster than wall street and increase their 25 ………… Secondly, they faced rejections or refuse from those 26 ……….. within the team. Lastly, the one who made mistakes had been punished by selling his/her stock share. |

Reading Passage 3 Academic IELTS Reading Test 87

Sunset for the Oil Business

The world is about to run out of oil. Or perhaps not. It depends on whom you believe…

{A} Members of the Department Analysis Centre (ODAC) recently met in London and presented technical data that support their grim forecast that the world is perilously close to running out of oil. Leading lights of this moment, including the geologist Colin Campbell, rejected rival views presented by the American geological Survey and the international energy agency that contradicted their findings. Dr. Campbell even decried the amazing display of ignorance, denial, and obfuscation by government industry and academics on this topic.

{B} So is the oil really running out? The answer is easy: Yes. Nobody seriously disputes the notion that oil is, for all practical purposes, a non-renewable resource that will run out someday, be that years or decades away. The harder question is determining when precisely oil will begin to get scarce. And answering that question involves scaling Hubbert’s peak.

{C} M. King Hubbert, a Shell geologist of legendary status among depletion experts, forecast in 1956 that oil production in the United States would peak in the early 1970s and then slowly decline, in something resembling a bell-shaped curve. At the time, his forecast was controversial, and many rubbish it. After 1970, however, empirical evidence proved him correct: oil production in America did indeed peak and has been in decline ever since.

{D} Dr Hubbert’s analysis drew on the observation that oil production in a new area typically rises quickly at first, as the easiest and cheapest reserves are tapped. Over time, reservoirs age and go into decline, and so lifting oil becomes more expensive. Oil from that area then becomes less competitive in relation to other fuels, or to oil from other areas. As a result, production slows down and usually tapers off and declines. That, he argued, made for a bell-shaped curve.

{E} His successful prediction has emboldened a new generation of geologists to apply his methodology on a global scale. Chief among them are the experts at ODAC, who worry that the global peak in production will come in the next decade. Dr. Campbell used to argue that the peak should have come already; he now thinks it is just around the corner. A heavyweight has now joined this gloomy chorus. Kenneth Deffeyes of Princeton University argues in a lively new book (“The View from Hubbert’s Peak”) that global oil production could peak as soon as 2004.

{F} That sharply contradicts mainstream thinking. America’s Geological Survey prepared an exhaustive study of oil depletion last year (in part to rebut Dr. Campbell’s arguments) that put the peak of production some decades off. The IEA has just weighed in with its new “World Energy Outlook”, which foresees enough oil to comfortably meet the demand to 2020 from remaining reserves. René Dahan, one of ExxonMobil’s top managers, goes further: with an assurance characteristic of the world’s largest energy company, he insists that the world will be awash in oil for another 70 years.

{G} Who is right? In making sense of these wildly opposing views, it is useful to look back at the pitiful history of oil forecasting. Doomsters have been predicting dry wells since the 1970s, but so far the oil is still gushing. Nearly all the predictions for 2000 made after the 1970s oil shocks were far too pessimistic. America’s Department of Energy thought that oil would reach $150 a barrel (at 2000 prices); even Exxon predicted a price of $100.

{H} Michael Lynch of DRI-WEFA, an economic consultancy, is one of the few oil forecasters who has got things generally right. In a new paper, Dr. Lynch analyses those historical forecasts. He finds evidence of both bias and recurring errors, which suggests that methodological mistakes (rather than just poor data) were the problem. In particular, he faults forecasters who used Hubbert-style analysis for relying on fixed estimates of how much “ultimately recoverable” oil there really is below ground, in the industry’s jargon: that figure, he insists, is actually a dynamic one, as improvements in infrastructure, knowledge, and technology raise the amount of oil which is recoverable.

{I} That points to what will probably determine whether the pessimists or the optimists are right: technological innovation. The first camp tends to be dismissive of claims of forthcoming technological revolutions in such areas as deep-water drilling and enhanced recovery. Dr Deffeyes captures this end-of-technology mindset well. He argues that because the industry has already spent billions on technology development, it makes it difficult to ask today for new technology, as most of the wheels have already been invented.

{J} Yet techno-optimists argue that the technological revolution in oil has only just begun. Average recovery rates (how much of the known oil in a reservoir can actually be brought to the surface) are still only around 30-35%. Industry optimists believe that new techniques on the drawing board today could lift that figure to 50-60% within a decade.

{K} Given the industry’s astonishing track record of innovation, it may be foolish to bet against it. That is the result of adversity: the nationalizations of the 1970s forced Big Oil to develop reserves in expensive, inaccessible places such as the North Sea and Alaska, undermining Dr Hubbert’s assumption that cheap reserves are developed first. The resulting upstream investments have driven down the cost of finding and developing wells over the last two decades from over $20 a barrel to around $6 a barrel. The cost of producing oil has fallen by half, to under $4 a barrel.

{L} Such miracles will not come cheap, however, since much of the world’s oil is now produced in aging fields that are rapidly declining. The IEA concludes that global oil production need not peak in the next two decades if the necessary investments are made. So how much is necessary? If oil companies are to replace the output lost at those aging fields and meet the world’s ever-rising demand for oil, the agency reckons they must invest $1 trillion in non-OPEC countries over the next decade alone. That’s quite a figure.

Questions 27-31 Academic IELTS Reading Test 87

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 3 In boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet, write

| YES | if the statement agrees with the writer |

| NO | if the statement does not agree with the writer |

| NOT GIVEN | if there is no information about this in the passage |

(27) Hubbert has a high-profile reputation amongst ODAC members.

(28) Oil is likely to last longer than some other energy sources.

(29) The majority of geologists believe that oil will start to run out sometime this decade.

(30) Over 50 percent of the oil we know about is currently being recovered.

(31) History has shown that some of Hubbert’s principles were mistaken.

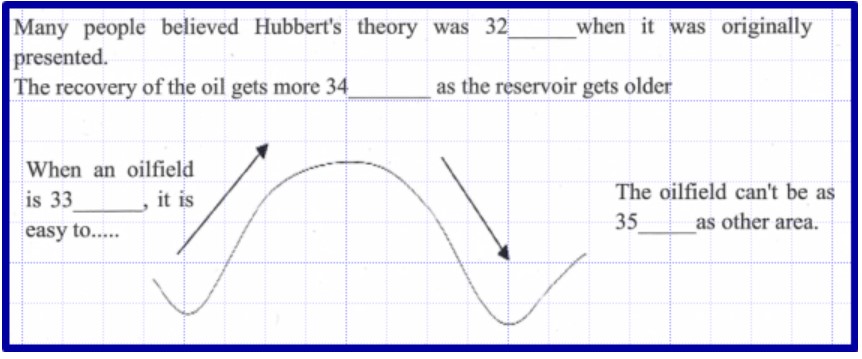

Question 32-35 Academic IELTS Reading Test 87

Complete the notes below Choose

ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 32-35 on your answer sheet.

Questions 36-40

Look at the following statements (questions 36-40) and the list of people below. Match each statement with the correct person, A-E.

Write the correct letter, A-E in boxes 36-40 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

(36) has found fault in the geological research procedure

(37) has provided the longest-range forecast regarding oil supply

(38) has convinced others that oil production will follow a particular model

(39) has accused fellow scientists of refusing to see the truth

(40) has expressed doubt over whether improved methods of extracting oil are possible.

| List of People

(A) Colin Campbell (B). M. King Hubbert (C) Kenneth Deffeyes (D) Rene Dahan (E) Michael Lynch |

For Answers Academic IELTS Reading Test 87 Answers

Pages Content

Discover more from IELTS Fever

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.